I first noticed them in a number of restaurants around Yangon: rusted old tin signs in still-vibrant colors advertising a wealth of different products from whiskey to baby formula. They were evocative of a time and place that I knew very little about.

Some were familiar – advertisements for European imported items the likes of which I had seen in the modern-day shopping malls of Yangon: Staedtler pencils, Nestle coffee, Horlick’s malted milk, while others were for brands that had long since ceased to exist (Ebensen’s Danish butter, Bile Beans, and Sanatogen “brain tonic”). In addition, there were a number of local and Asian brands I recognized from the supermarket, such as the ubiquitous Tiger Balm, and others I didn’t (Tea Pot Brandy, anyone?). Many of the signs appeared in two or three languages (in the case of Tiger Balm, in four: Burmese, Mandarin, English, and Malay), and as such they spoke to a multilingual audience.

I was intrigued, and as I came to study Myanmar’s colonial history, what were initially pieces of quaint décor took on a new and significant meaning for me as some of the only remaining evidence of Burma’s distinctive cosmopolitan past.

At the turn of the nineteenth-century, so the story goes, British Burma was exporting natural resources like rubber, teak and petroleum to the West and importing European manufactured goods. But what few people know is that gradually as the century progressed domestic Burmese manufacturing took on a more important role. Though always smaller than the import trade, Burma did produce new products for the regional market. For instance, Tiger Balm was first created in Burma in 1870, when an apothecary passed on his secret recipe to a pair of Chinese brothers Haw and Par, who began to market the analgesic all along the Straits of Malacca and even further afield to Europe and China. They amassed a great fortune and became philanthropists, building (among other charitable ventures) a memorial hall (still standing) at the Yangon Centre for the Blind, complete with the brand’s logo, a leaping tiger, over the entrance.

A quick internet search turned up a number of other local manufacturers making products for the Burmese market. They were the remnants of a Burmese industrial era gone-by: the Dawood Match Co., Imperial Waters, Burma Enameled Iron Wares Ltd., Bo Ohn Thee Toy Company and the Burma Biscuit Factory to name a few. Moreover, many of them proudly claimed to be “Made in Burma” a slogan that was distinctly hard to come by in the modern-day supermarkets of Yangon. Later on, a glance through the book Twentieth-century Impressions of Burma, published in 1910, revealed several other local companies manufacturing at the time: for instance, in Rangoon alone the Phoenix Coach Works made “dog carts, buggies, gharries and victorias”, Misquith and Co. made pianos and the Diamond Co. made ice and aerated water.

The largest market, however, was still for imported goods and it was in this area that advertising began to play a major role in dictating the Burmese encounter with modernity and the West. In order to create a demand for foreign products, foreign import firms began to try to appeal to the Burmese consumer (at the time, foreign companies rarely had advertising staff, and so they left the marketing of their products up to the local distributors, often Burmese).

In her book Refiguring Women, Colonialism and Modernity in Burma, Chie Ikeya suggests that these firms marketed their products to Burmese consumers using a new rhetoric of “modernity” and “science”. Foreign luxuries could, seemingly instantaneously, transform the Burmese customer into a paragon of good taste and health. To give one example, this advertisement for “Waterbury’s Compound” brand of cough syrup depicts a Burmese family in a spotless home. Mother and father wear the latest fashions, while one child plays with a toy car. The illustrator has even included a radio at the center of the room. The by-line reads: “may every family have a clear conscience when it comes to health”. The message is not only one of domesticity and better living through science, but the ad (with the radio and toy car) also hints at the promise of a new Burmese modernity in which the consumer need only buy the product to participate.

At the same time, the “foreign” was becoming increasingly popular in Burmese advertisements. Foreign English and Scottish products held a certain cache, as suggested by an “Imperial” mineral water sign that boasted its product came from a “trademarked Scottish Company”. In another ad, Burmese consumers were told that in order to keep up with the rest of the world they had to buy Model T cars. In fact, the ad stated, model T’s were already popular in Myanmar, so those without one were behind their neighbors. The desire of some Burmese people to keep up with other countries must have been great and Ikeya tells us that advertisements like these “insinuated…that those not using the advertisers’ products were falling behind the times,” the so-called “modern age” or the khit kala.

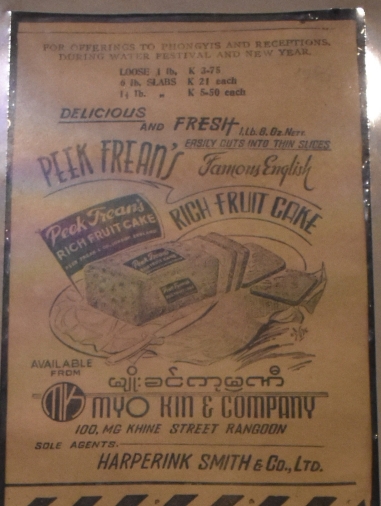

But clearly not all Burmese buyers were convinced and advertisers were pushed to market foreign goods in more and more far-fetched ways. Take for example this almost comedic ad for “Peek Frean’s Famous English Rich Fruit Cake” that suggests it is perfect “for offerings to phongyis (monks) and receptions during water festival and new year.” This strange adaptation of a foreign product for the Burmese market was not unusual, but whether or not Burmese consumers would go in for it was an entirely different question (as many modern Western brands new to Asia have discovered, what works in one place may not work in another). At the end of the day, the Burmese consumer also decided on what he or she wanted to buy, thereby dictating Burmese tastes and, ultimately, the path of Burma’s entrance into modernity.

Burma Biscuit Factory

LikeLike

Fantastic. Would you allow me to share these pictures on Facebook while also crediting you?

LikeLike