Any visitor to a pagoda or Buddhist shrine in Myanmar today is likely to encounter a sign at the entrance simply stating “Footwearing Prohibited.” Despite what it seems, this is not an injunction to amputate your own limbs, but a warning to remove your shoes before entering the pagoda or monastery compound. It is common in many Asian countries to remove your shoes before entering a building, but in Myanmar this rule extends to the outdoor areas of Buddhist sites as a sign of respect to the Buddha and the legacy of his teachings, the sasana. These signs are near ubiquitous at pagodas throughout the country, and, if you forget to remove your shoes and socks, a friendly caretaker or Pagoda trustee will usually quickly remind you to do so.

The rule is in fact codified in Burmese law under Section 13(1) of the Immigration Act, in which foreigners can be prosecuted for not adhering to Myanmar customs during their stay in-country. The punishments can be quite severe, as in the case of a Russian tourist who, in August of last year, refused to remove her shoes at several religious sites in the ancient capital city of Bagan, despite numerous requests from the authorities to do so. She was arrested and given the choice of a $500 fine or a month in prison. She chose prison and her sentence has since been extended to six months with hard labor for “defaming the sasana.”

But why is Myanmar so strict about footwear in pagoda compounds, especially when its neighbors Thailand and Laos only require visitors to remove their shoes inside of the shrine itself? Many natural tourist destinations in Myanmar such as caves and mountaintops are in fact holy sites and therefore require the visitor to go barefoot. In my travels I have often found myself squelching through mud and betel spit, walking up a mountain on hot gravel, or slip-sliding down a poorly-lit cave all in my bare feet. Why does the rule extend to places like these? And why such high punishments for breaking it?

The answer, of course, lies in the country’s colonial past, and, specifically, in two separate but equally important events: the growth of Buddhism as a religion and the struggle for national independence. When the British arrived in Burma in the late eighteenth-century they were keen to display their country’s power and to entice the Burmese to trade. First, however, they would have to master the Byzantine codes of conduct and elaborate rules of respect of the Burmese court of Ava.

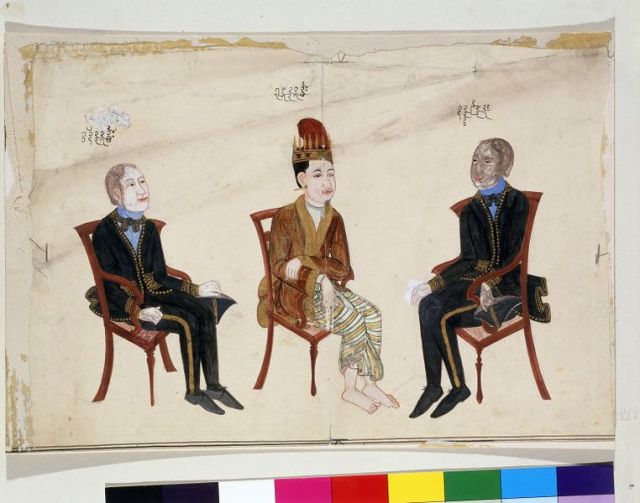

For instance, no envoy was allowed into the Burmese King’s presence without first removing their shoes and then prostrating themselves before the monarch in a deep bow called a shiko. The established narrative has it that the British were terrible at doing this; being uninterested in the local customs, they ignorantly stepped shoe-shod all over Burmese tradition and law.

But this narrative is only partly true. Yes the British were callous, but the reason for their disrespect was not ignorance. As the journals of Henry Burney, an early British envoy to the Court of Ava show, British disregard for local custom was often a strategic power-play to wear down the sovereignty of an Eastern monarch. Traditionally, envoys to the King had been made to remove their shoes “in the dirt or hard gravel of public streets, a hundred paces before you come to the spot where the king may be sitting.” But following the British territorial gains in the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824-1826), Burney had gotten the rule reduced to “the foot of the hall of audience steps” and hoped that with a bit more cajoling “the remaining space between the steps and the hall itself might [be] dispensed with.”

Eventually, the British would take the whole of Mandalay palace for themselves, but this process of wearing down the rules of respect allowed them to apply gradual pressure on Eastern rulers like the Burmese king while at the same time appearing to be the guiltless party. The neighboring Thai king Mongkut (of The King and I fame) was able to circumvent the problem altogether by allowing Europeans to wear shoes in his presence, thereby taking the diplomatic upper-hand and at the same time retaining his sovereignty. But in Burma, the question of wearing shoes would become a stand-in for debates about trade, power, and the deeply-fraught encounter with the West. Later on, the controversy would give the British colonial government in Lower Burma the opportunity to begin separating Buddhist religion from the state and society, thereby further weakening the old regime.

This approach was perhaps so effective in Myanmar because of the deep, enduring ties between religion and the state. In Theravada Buddhist cosmology, the King is the heaven-ordained defender of the sasana and all his subjects are required to prostrate themselves before him as they do before images of the Buddha. In return, he supports the monks and the people as an act of merit-making. In this universal model, there is no society separate from religion or the state: all three are fused.

In Burma, the British quickly identified this blending of state/society/religion as a powerful tool of Burmese resistance and so they attempted to undermine it as best they could. As Alicia Turner has shown in her book Saving Buddhism, when Burma fell to the British in 1885 and King Thibaw went into exile, the colonial government removed direct state support for the monks and pagodas according to a policy of separation of church and state that they imported from India.

But by treating Buddhism in Burma as just another religion alongside Islam and Christianity, they inadvertently sparked a crisis within Burmese Buddhism itself. Without the King, who would feed the monks and who would look after the Buddha’s sasana? Who would pay for the scriptures to be painstakingly copied? Turner says that the crisis that followed saw ordinary Burmese citizens leading the charge alongside the monks to revive the Buddha’s teachings and reclaim control over their moral universe. The mounting anxiety about the decline of the sasana (as referenced in my earlier posts) led to an outpouring of donations, a range of ritual and scriptural reforms, and the growth of Buddhist lay associations and schools all across the country – a Buddhist renaissance of sorts.

Despite this newfound agency, it was the British, not the Burmese, who would set the terms for what constituted proper conduct and respect, and they deemed that each of Burma’s ethnic groups would show respect in the way that was “traditional” to their culture. What was “traditional,” of course, would again be determined by the British. Therefore, Europeans would remove their hats, but not their shoes before entering a building or pagoda compound; Burmese their shoes, but not their hats. Early photographs of Europeans “on tour” at various holy sites in Myanmar show them wearing shoes – a highly disrespectful act in the eyes of Buddhists – as well as hats, highlighting the degree to which the rules were really just a double-standard in favor of Europeans.

The first challenge to this state of affairs actually came from within the Buddhist clergy, or sangha, itself. Turner highlights the case of the Okpo Sayadaw, a highly venerated Buddhist monk, attempting to make a point about the importance of the inner moral life over outer ritual when he mounted the stairs at the Sandawshin Pagoda in Pyay in 1892 wearing sandals.

This act would spark a series of debates among Burmese Buddhists about whether or not it mattered if other people wore shoes to the pagoda, as long as the worshipper’s heart and mind were orientated towards prayer and doing good deeds. One side advocated intention rather than action; the other argued that wearing shoes at the pagoda was a sin that affected the karma of everyone around and threatened the sasana. This group even went so far as to argue that non-believers should not be allowed in to the pagoda at all, as was the custom with mosques. In the end, the Sayadaw’s stunt had the desired effect. The question of wearing shoes in pagodas had been raised amongst Burmese Buddhists and it would soon become integral not only to the definition of Buddhism as a religion but also to the Burmese struggle for independence from the British.

The “Shoe Question,” as it came to be called, resurfaced again in 1901, taking on a new racial guise. In that year, the Irish-born itinerant Buddhist monk U Dhammaloka challenged an off-duty Indian police officer on the platform at the Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon, demanding that he remove his shoes. Dhammaloka, no doubt, felt that as a Buddhist and a European he could make the Indian officer remove his shoes. Indians traditionally removed their shoes at pagodas, but this man was an employee of the government. The altercation led to a series of reports and a newspaper controversy over the so-called “Shoe Question.”

The authorities immediately asserted that what was implicitly being discussed was the question of Burmese independence, even though the question of shoes in pagodas had been a subject of debate within Burmese Buddhism for some time. Nevertheless, in the following years, more and more Buddhist monks began challenging shoe-shod Europeans on pagoda platforms, and in 1918, the Young Men’s Buddhist Association (YMBA) met to draft a resolution that endorsed removing the dispensation for Europeans at pagodas throughout the country. Pagoda trustees began complying with the YMBA resolution and removed the exemption for Europeans from their signs. The “Shoe Question” had become political. In protest, the government argued that with the First World War raging, the actions of the pagoda trustees would cause sedition. Turner tells us that the two sides went back and forth, and under increasing pressure from the public, the government reluctantly gave in to the pagoda trustees in 1919.

Immediately afterwards the European community went on the defensive and began boycotting the pagodas, but the initial foray had been made, and it would only be a matter of time before the independence movement gained significant support among the Burmese Buddhist population. If the Burmese could change the law regarding footwear in pagodas what else could they change? Perhaps more importantly for our question, the relationship between Buddhism and Burmese nationalism had been cemented for good. From then on, the fight for Burmese independence would be dominated by Buddhist rhetoric and vice versa.

This fusion of Burmese nationalism and Buddhism lingers on in Myanmar to this very day in the form of laws that are designed to maintain and protect the Buddha’s teachings. Recently, tourists have been deported or jailed for showing disrespect to the Buddha, ranging from a Spaniard who was detained and advised to leave the country for having a Buddha tattoo on his lower calf (a disrespectful place in Burmese thinking), to a British bar manager who was imprisoned for 30 months for creating a flyer with a picture of the Buddha in headphones on it, to a Dutchman who was jailed for three months for pulling the plug on an amplifier at a monastery event. The deeply interwoven relationship between Buddhism, Burmese ethnicity, and the state in Burma has exacerbated the various conflicts raging in the border regions, and makes simple tasks like getting a passport a nightmare for non-Buddhist, non-Burmese citizens. Ultimately, the question of wearing shoes in pagodas is not one of simple “custom” or “tradition,” but has always been a stand-in for questions of Burmese sovereignty, xenophobia, and Myanmar’s geopolitical place in the world.

Sources:

Alicia Turner. Saving Buddhism: the Impermanence of Religion in Colonial Burma, (2014).

G.T. Bayfield and Maj. H. Burney, “Historical Review of the Political Relations between the British Government in India and the Empire of Ava” (Calcutta, 1835).

great post, so true, just makes me laugh and think in the west about shoes in the house o at the door….

LikeLike