Today I’d like to talk about two monuments that represent, respectively, a bit of Britain in Burma, and a bit of Burma in Britain.

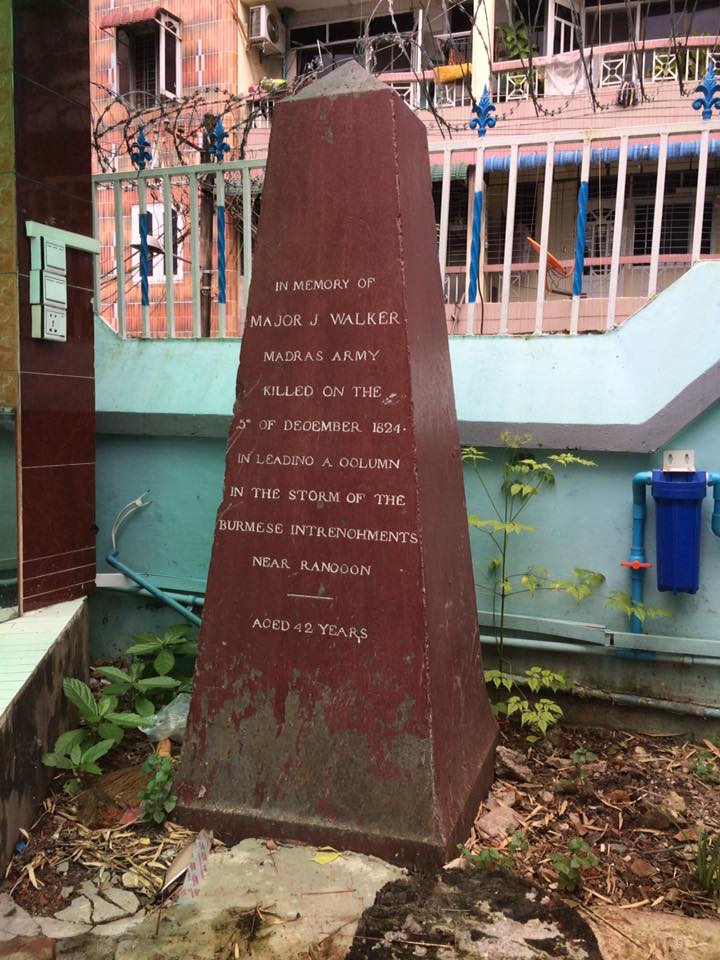

The first can be found down a narrow side-street in Yangon in the grounds of the St. John the Baptist Catholic Church. A large red pyramid of laterite rock, it is a monument to one Major J. Walker of the Madras Army, who died storming the stockade at Rangoon (Yangon) in the First Anglo-Burmese War of 1824. It is likely that the tombstone was moved here from the English Cantonment Cemetery near Kandawgyi Lake when the Burmese military took over that site in the 1960s [Correction 3/31/25: The Cantonment Cemetery was actually bulldozed in 1995].

The First Anglo-Burmese War pitted the forces of the British East India Co. and their Indian allies against the mighty Burmese Empire which had just completed a period of great expansion, defeating the kingdoms of Assam, Manipur, Siam and Arakan in quick succession.

Burmese troops had been making incursions into British Bengal in the area of Chittagong and the “Honourable Company” simply could not abide this violation of its liberties any longer. The British landed at Rangoon and promptly attacked the Burmese forces, who put up a strong defense, but were ultimately defeated. The War would drag on until 1826 with the Treaty of Yandabo, in which the Konbaung kings were forced to cede the provinces of Arakan, Assam, Manipur and Tanintharyi to the British and pay an indemnity of 1 million pounds.

This was a Pyrrhic victory, however, as the fighting had already cost the British 5-13 million pounds, precipitated economic collapse in India, and left behind 15,000 British and Indian dead. One of those casualties, no doubt, was the late Major Walker, aged 42 years at the time of his death.

His sacrifice to the Crown, and that of others, would be commemorated in similar monuments throughout Burma and India, literally inculcating the British victory onto the Burmese landscape. Within thirty years, Rangoon would fall into British hands and be completely re-designed in the manner of a European city to house a foreign population of Europeans, Chinese, Indians, Armenians and Jews, becoming barely recognizable in the process.

But just as Britain’s global conquest would have a lasting effect on the geography of Burma, scattering it with the physical markers of British dominion, so too would the influx of wealth from Burmese and other colonial possessions change the landscape of Britain, swelling the port cities, filling the coffers of the British landed gentry and resulting in a profusion of museums and monuments to the British imperial endeavor.

One of these monuments remains today on the North Terrace at Windsor Castle (the traditional home of the British royal family). It is a large bell from Mandalay that was seized by the British during the Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885-6, flanked on either side by two French and Portuguese cannons, also taken from Mandalay. The British Empire was not above stealing and displaying such spoils of war and Burmese artefacts (thus purloined) fill the collections of museums throughout the country and the Western world today.

In the case of the bell at Windsor, it originally hung in the Mandalarama Monastery in Aungmyethazan Township in Northeast Mandalay where it would have been rung three times by worshipers after venerating the image of the Buddha (once for the Buddha, once for his followers, and once for his teachings).

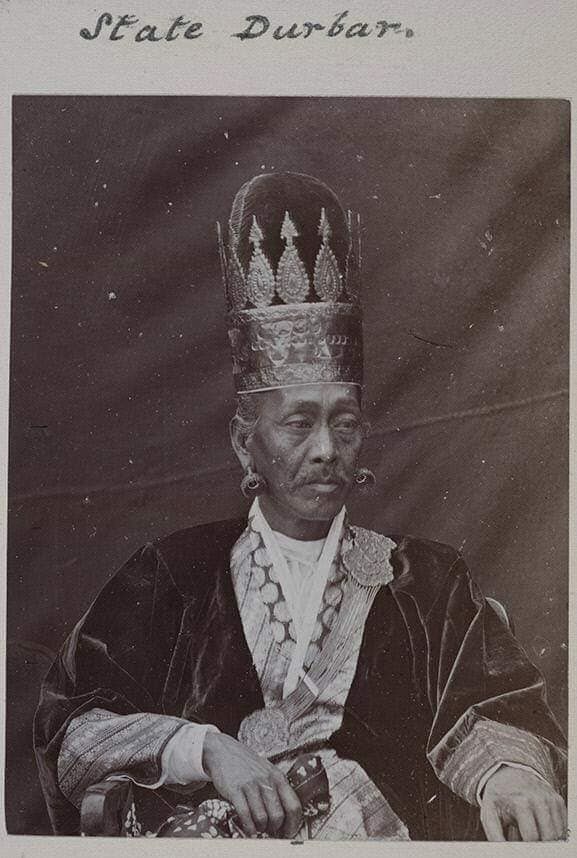

The bell has an interesting provenance. It was donated to the monastery by the Khampat Mingyi, one of the chief ministers of the Burmese Konbaung Dynasty (1752-1885), in 1878. The Khampat Mingyi was the leader of one of several warring factions in the hluttaw or parliament under King Thibaw, the last king of Burma (Source: U Sein Maung Oo, Kaun Laun Sar “The Book of Bells” quoted at The Learners with Thirst for Wisdom at https://www.facebook.com/groups/410766139274726/?multi_permalinks=622299881454683&ref=share).

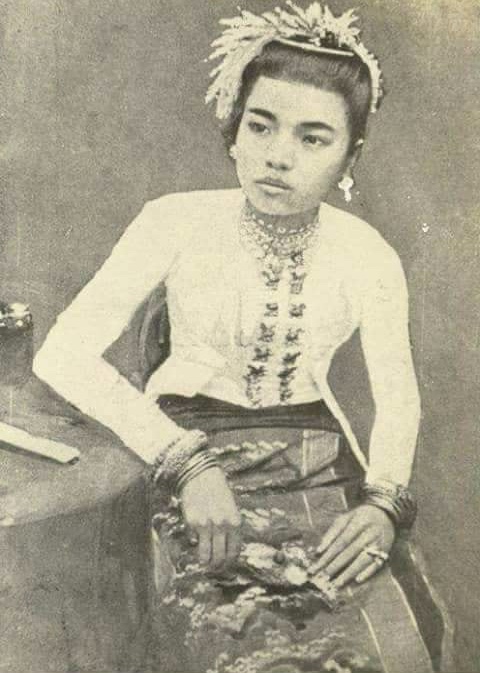

Scandalously, the Khanpat Mingyi’s granddaughter Daing Khin Khin was at the centre of a plot to break Queen Supayalat’s notorious hold over her husband Thibaw. Thibaw’s closest confidant, Maung Maung Toke, introduced Daing Khin Khin to Thibaw hoping that the King would be smitten and take the beautiful seventeen year-old as his wife. Thibaw fell in love with her immediately, but upon hearing of her husband’s infidelity, Queen Supayalat flew into a rage and quickly neutralized Maung Maung Toke, Daing Khin Khin and her entire family’s influence. The 17 year-old Daing Khin Khin was later executed. Supayalat was in fact unusual in the history of Burmese royalty not for her tenacity, but for insisting that Thibaw limit himself to one queen – herself (Source: Sudha Shah, The King in Exile).

When the British marched into Mandalay in 1885 they stole much of the King’s jewels, gold and royal regalia, and ransacked the holy pagodas and monasteries. Among this loot must have been the Windsor bell as well as an additional three bells taken by the 1st Battalion of the Royal Welch Fusiliers from the Atumashi Monastery and sent back to Britain. One of them is still on public display at Wrexham in Wales, another ended up at the Royal Welch Fusiliers Museum at Caernarfon Castle, and is not clear what happened to the third.

Many other specimens of Burmese art taken from Mandalay were displayed in museums, public squares and private collections throughout Britain, making the British public more knowledgeable about Burma, while at the same time reinforcing the bonds that tied Britain and Burma tightly together through the unequal logic of empire.

The English Cantonmen Cemetary near Kandawgyi Lake was moved after the 1988 uprising during SLORC Government in early 90″s, time when all cemeteries in town area or inside city limit were relocated. My grandparents, Chinese Catholics who were buried there, their tombs along with whatever left had to be moved to a new location outside of town. Doubt its in the 60s.

LikeLike