The city of Kolkata (formerly Calcutta) is the third largest city in India and the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal.

Up until 1911, it was also the capital of the British Indian Empire or Raj, which stretched from the borders of Afghanistan to the balmy jungles of Malaysia.

As Myanmar (Burma) was a province of British India from 1852 to 1937, it was ruled directly from the Government House in Calcutta right across the Bay of Bengal and then from New Delhi.

As such, colonial Burma possessed many educational, financial and cultural links with India (indeed, in 1900, half of the population of Burma’s principal seaport, Rangoon, were Indians).

Located only three days’ journey from Rangoon by ship, moreover, Calcutta became a kind of Mecca for Burmese and Burma-domiciled Indians to study, do business and relax.

The architectural and artistic remnants of this Burma-Bengal connection can be found throughout the modern city today – if we only know where to look.

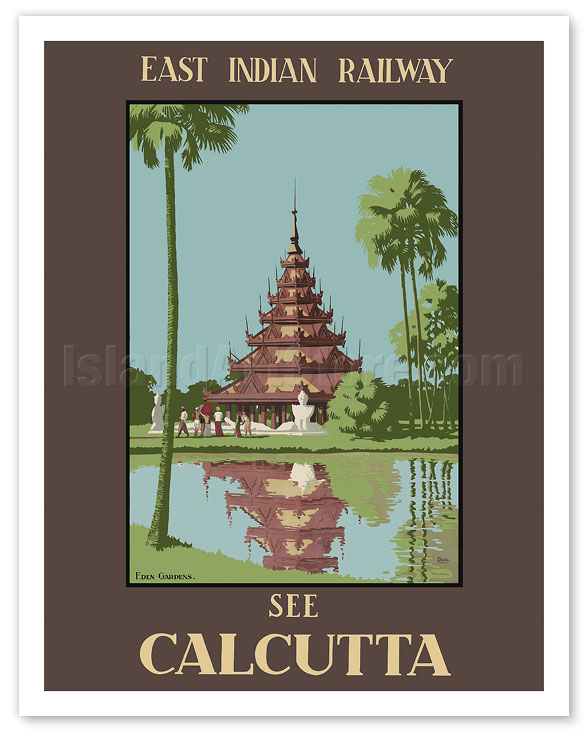

Burmese Pagoda – Eden Gardens

Hidden directly behind the massive Eden Gardens cricket stadium in downtown Kolkata stands a green, unassuming little park – a quiet oasis from the roar of the match-day crowds.

The stadium actually takes its name from the park and not the other way around.

Eden Gardens was first opened to the public as the Auckland Circus Gardens in 1840, and, in 1841, became Eden Gardens in honor of George Eden, the Governor-General of India from 1836 to 1842.

If you make your way to the back of the park and cross a little bridge to a man-made island, you encounter a seemingly incongruous sight:

A full-size Burmese pagoda.

Strictly speaking, this gilded teak-wood structure is not a “pagoda” but a tazaung, a kind of shrine or pavilion often found on the grounds of pagoda precincts in Myanmar.

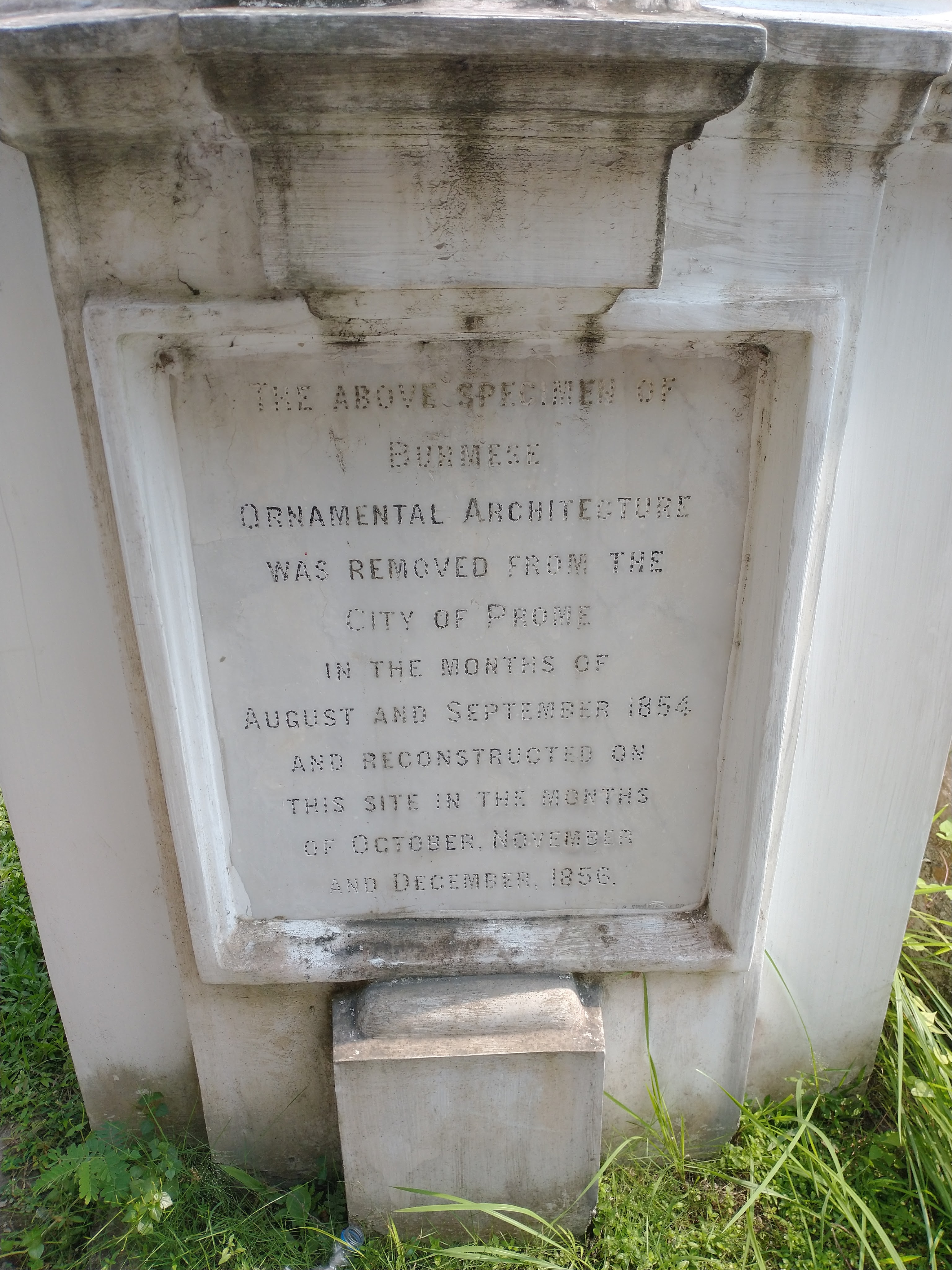

It is, however, original. The building was brought over from Prome (Pyay) in Burma in 1854 after the Second Anglo-Burmese War of 1851-2.

The British had fought the Second Anglo-Burmese War in the name of imperial expansion in Asia, and had won a territorial buffer for their colonial possessions in Bengal in the form of Lower Burma.

From this war they brought home many spoils to India, including the tazaung; it was set up in Eden Gardens in 1856 and has stood there ever since.

By 1923, however, the British Government had forgotten where the structure originally came from. There was an old stone tablet at its base, but this was largely illegible – so the Archaeological Dept. went looking through the records and rediscovered the origins of the Pagoda. A new tablet was then installed.

The tazaung was just one example of the loot the British brought back from their many wars of conquest in Asia after 1757, using Calcutta as their base.

Other artefacts included a priceless golden Burmese yatha or carriage which was displayed in London.

The “Burmese Pagoda” in Kolkata is an ornate and prominent reminder that the historical connections between Burma and Bengal run deep.

Second Anglo-Burmese War Grave – St. Paul’s Cathedral, Maidan

If you walk down the long Chowringhee Road, past the New Market and Park Street, almost to the bottom of the Maidan, you will encounter another stark reminder of the Burma-Bengal connection in the form of St. Paul’s Anglican Cathedral.

This magnificent church was built in the Neo-Gothic style in 1847, designed by William Nairn Forbes (1796-1855). It was the first Anglican cathedral in Asia.

This cathedral served the European community of Calcutta for over one hundred years and still serves the Indian Anglican Christian community.

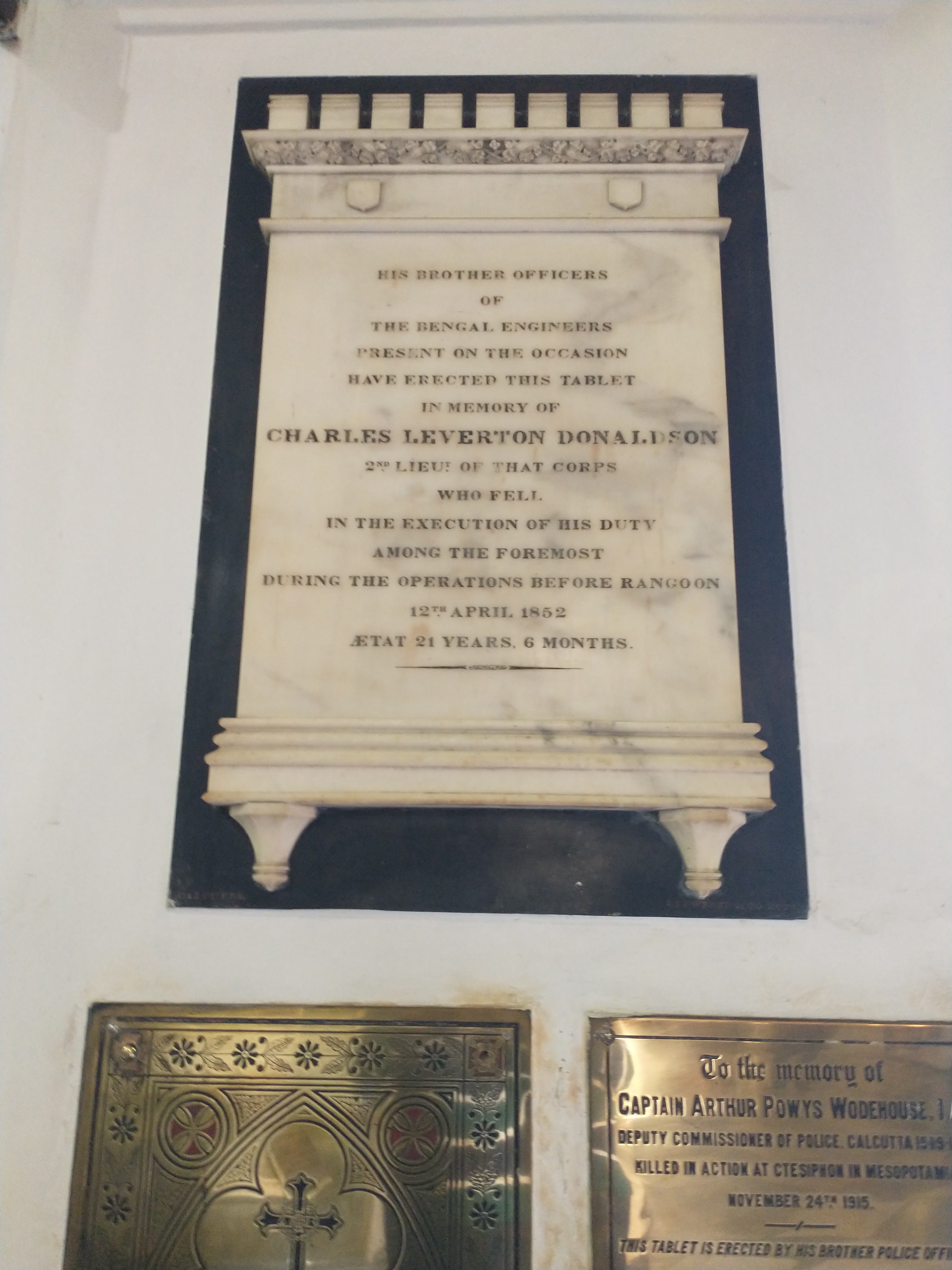

Within St. Paul’s large marble nave, one finds a veritable graveyard of tombs and plaques, and, amongst these is one of interest to Burma.

The inscription reads: “His brother officers of the Bengal Engineers/ present on the occasion/ have erected this tablet in memory of/ Charles Leverton Donaldson/ second lieutenant of that corps/ who fell in the execution of his duty/ among the foremost during the operations before Rangoon/ 12th April 1852/ Aetat. [his age] 21 years, 6 months”.

This 21 year old soldier fell in the first few months of the Second Anglo-Burmese War, when the British captured and decimated the Burmese town of Yangon.

They subsequently renamed the city Rangoon, redesigning it as a colonial port town on the model of Singapore.

Charles Leverton Donaldson appears to have also been related to the well-known British architect Thomas Leverton Donaldson (1795-1885).

It was not uncommon for British men to die young in India – from, as in Donaldson’s case, warfare, but also from ship-wreck or disease – and St. Paul’s is filled with such epitaphs marking the history of British imperial expansion in the region.

See my post on “A Tale of Two Monuments” below for examples of British war graves in Burma.

19th Cent. Burmese Shrine and Kalaga – The Indian Museum

Making our way back up the Chowringhee Road, we arrive at the Indian Museum – a stately Victorian building on two levels.

The history of this museum stems back to 1814, but the current building opened in 1875.

Holiday crowds jam the entrance and street hawkers attempt to entice you with their home-made wares.

After the Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885, when the British deposed the Burmese Konbaung Dynasty (1752-1885) once and for all and conquered the whole of Burma, a host of items from the royal palace at Mandalay found their way to the Indian Museum.

The royal Lion Throne of the Konbaung kings, for instance, was displayed in the Indian Museum from 1902 to 1948, before it was returned to a newly independent Burma.

If you go to the second floor of the museum today, to the Decorative Art gallery where the royal Burmese throne was originally displayed, you can still find a smattering of Burmese items including wooden statues, monastic offering bowls and an embroidered Burmese tapestry called a kalaga.

In and amongst these artifacts is an imposing wooden Burmese shrine with an ivory Buddha, likely from the 19th century.

The provenance of this piece is mysterious.

Next to it stands a “replica of the gateway of the Salin Monastery, c. 1895-1900” suggesting that the shrine might also be a replica of a Buddhist shrine in Burma.

But it is also possible that this shrine was part of the bequest of the Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon in 1902 and is therefore original — though we cannot be sure.

One thing is for certain, however: it is an amazing piece and exceedingly rare, even in Burma.

Judging from the lack of provenance on the museum plaque, the Museum appears to be blissfully unaware of the importance of the object it possesses.

The catalogue of The Arts and Crafts of Myanmar published by the Museum says nothing about it.

Myanmar Buddhist Temple – Central

If we leave the Indian Museum and hop on the Calcutta metro (the oldest system in India) at Park Street (make sure to get on the right gender car) change at Esplanade, and ride to Central Station, we emerge into the light in a small square.

On the Southern side of this square is a dilapidated little building with a metal sign that reads “Myanmar Buddhist Temple”.

It is a noisy location for such a sacred space – right at the heart of the old city.

Up the stairs we are greeted in Burmese by a Buddhist monk in Saffron robes.

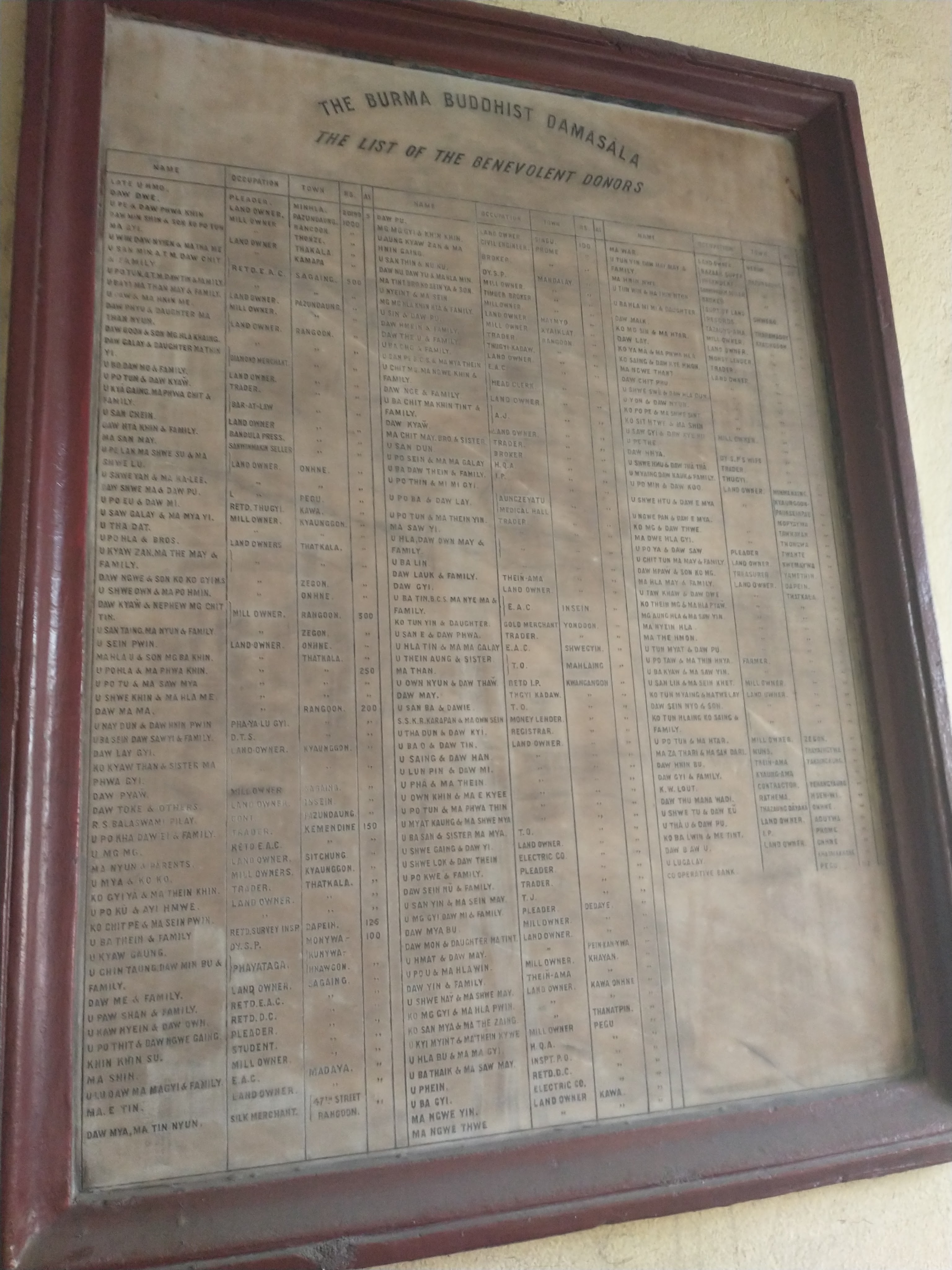

The space is not in fact a temple but a dhammasala or rest house for Burmese pilgrims on their way to the Buddha’s place of enlightenment in Bodh Gaya, Bihar.

It was founded by a wealthy Burmese colonial official – U San Min (ATM) – in 1927 and has been used for this purpose for almost 100 years.

Burmese students studying at schools and universities in colonial Calcutta have often stayed here as well.

On the wall of the stairwell hangs a list of the original donors (all Burmese) and at the back is a statue of the Buddha beneath a halo of neon lights.

The kindly young monk encourages us to visit Bodh Gaya and to follow in the footsteps of the Buddha.

With thanks and prayers we emerge back onto the busy Eden Hospital Road.

Searching for the Burmese “Academy” a “teeming hive of vice”

Now we have walked over 5 minutes to College Street…we are in search of the “Academy”, the notorious hostel where the Burmese students were supposed to have lodged while attending Calcutta University in the 1920s and ‘30s.

It was described by one Burmese writer during the period as a “teeming hive of vice” – no doubt due to the high proportion of young men studying far from home and out from under the watchful eye of their parents.

But we cannot find it anywhere.

Perhaps it was near the Eden Hindu Hostel in the shadow of Presidency College (a friend suggests)? The trail runs cold.

Instead, we find the famous College Street book-sellers who ply their wares on the roadside, and the snack-vendors making parathas and samosas and serving sweet hot chai in chipped ceramic cups.

Some of these cups come flying across the road and smash in the gutter when the customers are done with them.

The cuisine is reminiscent of Burma, where Bengali street-vendors introduced precisely the same sorts of foods in the 19th century.

Though we cannot find the old Burmese hostel, in a sweet cup of liquid chai we find a piquant reminder of the many enduring colonial connections that still link the city of Kolkata with its postcolonial neighbor Myanmar.